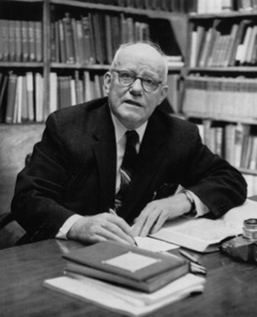

Strict scientific standards in pharmaceutical advertising were not widely adhered to in the early 20th century. The requirement that claims be supported by objective clinical and laboratory research resulted from a steady advancement in medical knowledge. But as it is with all evolutionary processes, certain persons were important in establishing the scientific model in medical advertising. Such a person was Harry C. Phibbs.

Looking back over our history, we can identify Phibbs as the first advertising executive to found an agency devoted to the creation of advertising that drew upon a product’s technical and clinical literature rather than following the promotional convention of the day to exaggerate a product’s benefits and to concoct imaginary virtues.

Phibbs brought this “ethical” approach to the business in 1921 when he started Harry C. Phibbs Advertising Co. with himself as the sole employee, $200 in the bank, and his wife as his secretary. His innovation was a rigorous scientific standard and also a concentration on prescription drugs. On the strength of these two qualities, he can be identified as the first in our field—the forerunner who laid the foundations for today’s specialized medical advertising agencies.

He opened his agency in Chicago and the geography was very important. The American Medical Association had its headquarters in Chicago, as it does today. Phibbs was helped greatly by an officer of the AMA, Dr. Morris Fishbein, who was a personal friend. The AMA, and Fishbein in particular as an editor of JAMA, had been waging a campaign against the specious patent medicines of the period.

The AMA had established a Council on Drugs, which ruled on which products could be advertised in its publications. It also had a system of copy clearance on the ads themselves. The job of dealing with the mass of questionable and often fraudulent advertising submitted to the AMA was daunting.

Fishbein, according to Phibbs’ son Brendon, came to his father with a proposition: “Harry, why don’t you start a professional medical ad agency that will bring us stuff we can believe and you’ll screen all of this for us?”

For Phibbs, who had a background in “ethical drugs” and advertising, it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity—just the chance he had been looking for when he had left Ireland for America.

Phibbs was from Dublin, where his family had once been part of the landed aristocracy (a section of the city is named Phibbsborough from a royal land grant). The Phibbses had fallen on hard times and Harry led a rough and tumble boyhood until a stern uncle set him on a different path. He became part of the intellectual fervor of the city, becoming a friend of Joyce and Yeats and a member of the famous Abbey Theatre group. But he felt Ireland was not for him and left for America, landing in Newfoundland in the depths of winter, virtually penniless. He put his artistic talent to work as a designer of stained glass windows, then, moved to Montreal where he worked as a stage manager, newspaperman, attempted to join the Mounties, and finally settled into a job as a sales representative for Burroughs Wellcome. The company transferred him to New York, where he joined the state’s 69th Infantry Regiment but, because he was married with two children, he missed going overseas in WWI, much to his disappointment.

Then, furthering his involvement in the drug business, he took a position with Vick Chemical Co. as the manager of its Greensboro, NC, manufacturing plant. His next stop was Chicago, where he was working for an ad agency when Fishbein approached him with the suggestion for his own agency and an offer of help with clients.

Phibbs started his agency as a counterweight to what he considered the “dishonest” element in healthcare advertising and throughout his career maintained a scrupulous scientific level in the work he produced and in the products he would accept. His sons Brendon and Roderic remember him coming home incensed with what he saw as objectionable advertising and manufacturers he felt were endangering the health of the public.

He once told a young copywriter, “You are not writing advertising. You are saving lives!”

His agency prospered and its standards and organization (for example, Phibbs had physicians on staff) greatly influenced the agencies that were to follow.

After so much early moving about, Phibbs put down deep roots in Chicago. He had a lifelong interest in photography and was active with the Chicago Camera Club, as well as the Businessmen’s Art Club and the Adventurers’ Club of Chicago. He greatly preferred Chicago and the American West to the East and, particularly, New York City, which he considered “too European.” Nevertheless, he had clients in New York, and to service them, he kept an apartment in Manhattan and for many years spent 1 week a month in the city tending to business and also enjoying its restaurants, theater, and museums.

He led an adventurous youth, was a successful businessman in a field in which he could exercise his interest in art and, at the same time, make a social contribution, and he took considerable pride in his two sons who, undoubtedly influenced by exposure to their father’s world, became eminent physicians—Brendon, a cardiologist and Roderic, a pediatrician.

Harry C. Phibbs died at 75 years of age in 1960. His agency was acquired by another Chicago agency, Frank J. Corbett, in 1970.