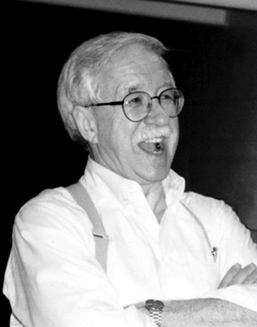

James McFarland began his career in medical advertising as a comp artist in the bullpen at Sudler & Hennessey (S&H) in 1960. There he worked under the legendary Herb Lubalin. Over the years at S&H, he assisted and learned from a number of other outstanding design talents, such as Ernie Smith and Dick Jones. Eventually, McFarland became associate creative director/art at the agency.

When he joined with John Lally and Ron Pantello to open Lally McFarland & Pantello (LM&P) in 1980, he took with him a vision of a creative-oriented organization. Through the influence of his personality and his example, this direction was established at LM&P.

All advertising agencies pride themselves on their creative abilities. The constant challenge in a competitive market is how to structure and nurture the proper mix of copywriters and designers, and their relationship to account service/marketing, to produce ideas that attract an audience’s attention and motivate purchase. McFarland, in conjunction with his partners, succeeded so well that some 6 years after his retirement, his imprint—emphasis on the creative—can still be seen at the agency.

It is hard to separate McFarland’s personality from the policies at LM&P that promoted an emphasis on working, above all, for the very best creative message. Central to a productive creative environment is an openness to contribution from all levels. The source of an idea does not determine its value. McFarland operated on this principle out of an innate respect for others, as described by someone who knew him well: “He created an environment that fostered creativity. He was receptive to other people’s ideas. Things didn’t have to revolve around one person’s ideas, but the best idea in the room.” Simply put—it was a creative meritocracy.

Also helpful in maintaining a productive creative atmosphere is the leader’s style in saying “no” without inhibiting idea generation. McFarland, who is basically a shy, gentlemanly person, was extremely good at turning things down without offending the creator.

His long-time collaborator John Lally describes him this way: “Jim was the easiest and the toughest man to work with I ever saw. He was easy because he was very encouraging. He would never just say, ‘Oh, that’s a terrible idea.’ He’d always give it a chance…[and] never really yelled about it a lot. He’d say, ‘You know, that just isn’t grabbing me.’ But [he was also] the most demanding. If it wasn’t perfect, it wasn’t going out.”

Advertising is a collaborative process and McFarland, who was uncomfortable with confrontations, excelled in the give-and-take negotiations that arrive at workable solutions—just as long as his sense of design values had not been compromised. His greatest collaborative challenge, however, was as peacemaker between John Lally (known for his strong opinions) and Ron Pantello (an equally forceful personality).

As Pantello tells it, “John and I would get fussing about something…creative issues, never about money or power…and Jimmy was always there to calm everybody down and get us moving in the right direction. Jimmy was always there as the cement between the three of us. John and I couldn’t have done it without him.”

Beyond his collaborative spirit and abilities to elicit ideas from his staff and manage creative egos, McFarland built strong creative departments by the work he himself produced. He was a designer of superb taste and innovation who, not surprisingly, worked well with copywriters who had standards as high as his own. Together they created award-winning and sales-building programs.

At S&H, he was assigned the Parke-Davis and Pfizer brands. With John Lally, he did campaign after campaign for Ayerst’s Premarin. He also successfully worked on minor brands that, without field support, depended heavily on nonpersonal selling like journal advertising. It was on such a “me-too” brand that LM&P got its start.

The product was Entex LA, a parity cough-cold product marketed by Norwich Eaton. The LM&P partners got the opportunity to pitch the business, won the account, and set up shop. The creative energy they brought to Entex LA propelled it to the top of its class and made the agency’s reputation. Important products like Macrodantin followed, as did other major prescription drug assignments. When Procter & Gamble acquired Norwich Eaton, the agency had a client with the resources and the appreciation of quality advertising to fund sizable programs for healthcare and dental products. The agency had established itself on the basis of its creative credentials of which the working relationship between McFarland and Lally was the foundation.

McFarland retired in 1985, but is still active as a designer and illustrator. And, once again, he is in a productive collaborative relationship. This time the writer is his wife, with whom he is producing children’s books.