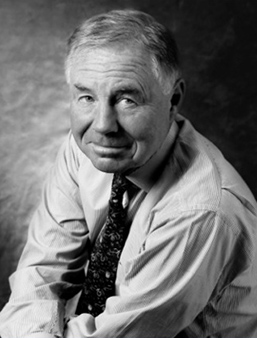

Mike Lyons began his advertising career with the consumer agency Doner Harrison in the early 1960s. He then moved into the prescription world at L.W. Frohlich in 1968. In 1970, he joined Sudler & Hennessey, putting in 9 years when the shop was experiencing a creative flowering fueled by the output of an impressive staff of writing and design talent. This environment saw Mike going from learner to leader in a few short years. He become executive director of design in 1972 and was an important part of the excellence of the agency’s creative product as the art director on award-winning ads for Pfizer’s Navane, Antivert, Diabinese, Sustaire, and Vistaril.

It was through the work on these products that he became friendly with William Steere, then heading up Pfizer’s Roerig Division. When management at S&H chose to take on the breakthrough beta-blocker Inderal in the face of its assignment on Pfizer’s antihypertensive Minipress, the ensuing product conflict gave Lyons—along with John Dorritie, the Pfizer account supervisor—the opportunity all advertising people dream of: the chance to start their own agency. Steere was receptive to a Minipress pitch; they won the account with their creative ideas; and, in 1979, Dorritie & Lyons opened for business.

There couldn’t have been a better time to become a Pfizer ad agency. Dorritie & Lyons (later Dorritie Lyons & Nickel) became the lead agency on such important products as Procardia (the first calcium antagonist introduced in the United States), Feldene (an improved NSAID), and the antibiotic Cefobid. These hugely successful brands propelled the agency from a boutique to a major prescription marketing and creative organization. Assignments from other pharmaceutical clients followed.

Then, in the midst of a rising billings and creative accomplishment, John Dorritie died unexpectedly of a heart attack in 1991. Lyons became chairman/CEO and creative director and under his leadership the organization maintained its momentum. In 1994, the agency merged with Lavey/Wolff/Swift to become Lyons Lavey Nickel Swift with Lyons as chairman/CEO and continuing as creative director.

Lyon’s forte as a designer has been his ability to take complex subject matter and crystallize its core information into communicative, compelling, and memorable graphics for ads and sales materials.

“You could whip by one of Mike’s ads and in a second or two or three, you knew exactly what it was telling you,” Al Nickel explains.

Bruce Richmond agrees, commenting, “The creative quality that made Mike unique is that while most of us think in words, Mike thinks in graphics.”

Fellow designer Tom Velarde remembers Mike in meetings: “He always had a pad and a Pentel with him and he would be scribbling all the time. People would be talking. Mike would be scribbling, doing thumbnails that he thought were pertinent and would get the idea across.”

Like many art directors, Lyons is not loquacious and has been described by his colleagues as a “private person,” who concentrates what he has to say into his designs. However, he is far from a one-dimensional creative talent and has written more than his share of winning headlines or returned copy to the writers until it was done to his satisfaction. When he achieved it, he was not ready to compromise.

Jim Stroup explains, “It’s not stubbornness, but he was very insistent about what he believed.”

Adds Al Nickel, “One of his abilities was to do what was best for the brand.”

Lyons could be intense in maintaining his position on what he felt needed to be said about a product. Matters would eventually be resolved, says Nickel, in the “calmness the next morning,” but Lyons would hold out as long as possible for what he thought was right.

“He was passionately competitive in everything he did,” says Richmond. “Whether it was rooting for the Boston Red Sox or whether it was developing an ad campaign or playing a game of tennis, he brought 150 percent to the table every single time. He was never satisfied with mediocrity.”

Lyons is very athletic, excelling at tennis and golf. On this point, William Steere says, “He has extraordinary hand/eye coordination and very quick reaction on the level of champion tennis. When you see him play tennis, you understand how competitive he is.”

Mike is also proficient at scuba diving and spearfishing.

The picture that emerges of Lyons is of an extremely talented creator of advertising concepts and campaigns of superb taste and design values, a reserved person passionate about his work with an athletic side in which his competitive nature finds full expression. But this is not the whole story.

“He took it all very seriously…but he had the ability to laugh at himself,” says Richmond, “which is something you have to do in advertising. Competitive, but a warm, compassionate person.”

“He was extremely loyal to his ideas,” Velarde confides, “and to his people, to his suppliers, and to his old friends. He was a fun-loving guy. There were a lot of things people never knew about Mike. But when you got inside to know the guy, you found he was very different. He had a great, great sense of humor. And to prove that, he’s still a Red Sox fan. If that’s not a sense of humor…and a sense of loyalty, what is?”

Lyons retired from Lyons Lavey Nickel Swift this past year. His work is included in Medicine Ave. as representative of some of the best in 60 years of prescription advertising. Further evidence of his abilities can be seen in the book’s styling, to which Mike contributed as a member of the Medicine Ave. publication team.